There are many ways to talk and think about landscapes such as drylands, deserts and rangelands. At the 7th Oxford Interdisciplinary Desert Conference in March, I witnessed research on and about drylands, or ecosystems that are defined by water-scarcity, being expressed in different ways across disciplines, perspectives and geographies. Compared to the first time I attended this conference in 2017, I noticed that poetry may be gaining some space in the academic world as a tool in research.

Some notable examples I came across this time:

Joanna Allan’s processes of poetic inquiry in Western Sahara with the Saharawi, in collaboration with Benjamin Brock’s expertise on physical geography, to integrate climate information from oral traditions into climate modelling. Meteorological data scarcity is extreme in Saharan Africa, and what is not measured almost falls off the radar in this day and age. But rather than pushing solely for more climate data through weather sensors or climate simulations, this collaboration acknowledges the value of insights from people’s histories. Saharawi oral traditions include historic weather events recorded in descriptions of grazing patterns, and these can shed light on how climates have shifted in areas where climate data is scarce.

The collaborative project Desert Disorders examines the post/colonial inheritance of desert discourses about Somaliland and the Thar desert. This project includes Christina Woolner’s work as a social anthropologist on echoes of the landscape of the desert through the poetry of people from the Somali diaspora in the UK.

Abdul Wahid Khan’s use of poetry and music as a grounded research method in Chitral, Pakistan, to access the emotional and experiential dimensions of local life. The work reveals how poetry has historically functioned as a source of resistance against the nationalization of commons.

Michael Macdonald’s work on ‘Desert diaries’ does not use poetry, but he signals how early-forms of literacy, through two-thousand-year-old inscriptions on basalt rocks in the basalt desert (ḥarra) of north-eastern Jordan “like pages from thousands of diaries”, paint a vivid picture of the circumstances, feelings and rumours from the desert.

It’s incredible that poetic inquiry can be used to reframe climate change impact from a Saharawi outlook by integrating different knowledge systems, speak about the Somali from a diasporic perspective, understand Chitrali resistance against the nationalization of the commons, and appreciate two-thousand-year-old everyday descriptions of the settled areas ruled by the Nabataeans, the Herodians and the Romans.

Poetic inquiry

But the Swiss-army-knife appeal of poetic inquiry for me is in following the emerging dialogical process that comes from poetic encounters, and thinking about how this can be represented. María E. Fernández-Giménez’s work Grazing the Fire: Poetry of Rangeland Science is an excellent example of how poetry can be used as a tool by rangeland scientists to communicate what would otherwise be expressed in the format of published scientific research papers.

My presentation at the conference focused on how we render the process of poetic inquiry visible, exposing different voices and different epistemic spaces, to cognitively shift our understanding of ‘the desert’. Beyond poetry as method, the didactic and pedagogic element of poetry becomes important in research.

Based on my own journey on poetic inquiry in Douz, southern Tunisia, where I focus on desert imaginaries, I am exploring how to best represent these different epistemic spaces visually – outside of academic articles and parlance – as it can be used as a tool to bring together researchers- activists- artists and ‘farmers’. With the Tunisian Observatory on Food Sovereignty and the Environment, the idea is to develop this further, recognising that peasant struggles and histories are often voiced orally.

In a way this exploration echoes Joanna’s in her recently published book Saharan Winds: Energy Systems and Aeolian Imaginaries, where she highlights the “potential offered by nomadic, Indigenous wind imaginaries for contributing to a fairer energy future” within the “wind-fuelled oppression of colonial energy systems” in Western Sahara.

Similarly, poetry from Douz – renowned for its poetry competitions performed at the yearly international festival of the Sahara – can contribute to a fairer, more wide-angled vision of a tourism and energy future in Tunisia, especially as massive ongoing solar farms and green hydrogen extraction speculations quietly aim to export energy to Europe.

This work ties with Brahim El Guabli’s work on Saharanism – a conceptual lens that draws from Orientalism to talk about the racializing and extractive imaginaries that frame deserts as empty, threatening and lifeless spaces. The way in which emptiness within the desert’s socio-ecological context is both romanticised and feared and serves as a geographical blank canvas upon which cultural and political views can be painted on is extremely interesting to me. I am slowly exploring how contemporary poetry from Douz foregrounds these desert imaginaries.

Comics

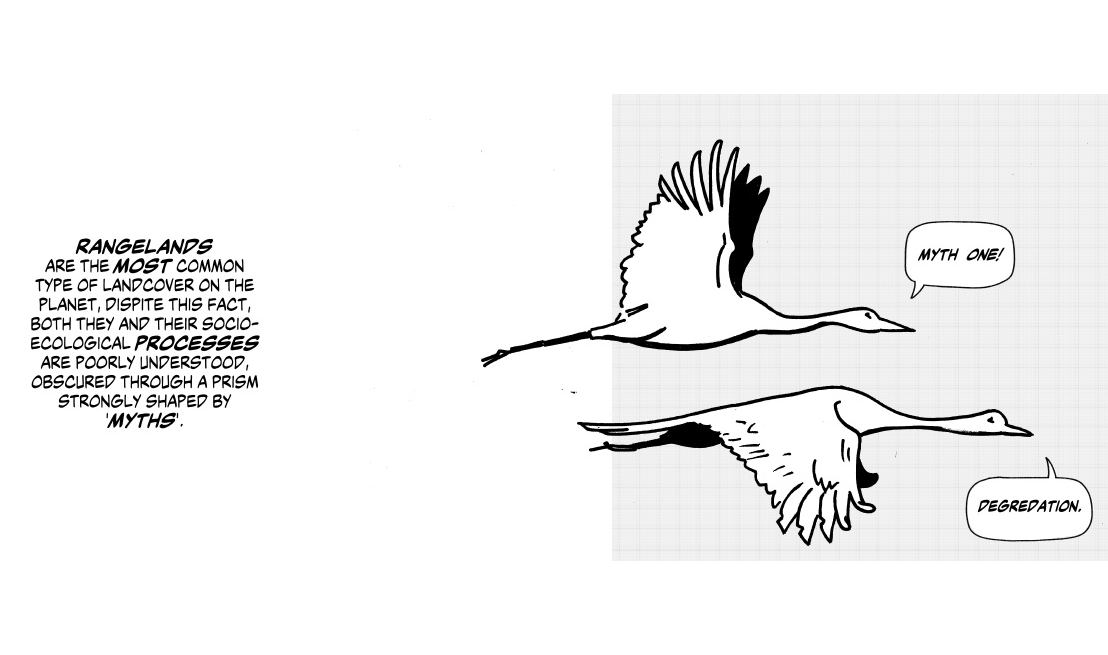

Comics are another story-telling tool that helps engage with different disciplines across different contexts. In the REPAiR project, comics are used to nuance the myth-making process on grasslands. By ‘myths’, we refer to widespread received wisdoms, unquestioned assumptions and dogmas that have shaped public perceptions, scientific knowledge, policy regimes and approaches to intervention.

Despite being overgeneralised, counterfactual or just plain wrong, myths continue to persist in discourses about pastoralists and rangelands across different scales – regionally, nationally and locally.

Visualizing how these narratives persist in ways that capture context, scale, temporality and dynamic variability is important for knowledge co-production and to produce counter narratives. As we crowd-source different experiences and narrations of different myths, we are working with Tim Zocco to co-create beautiful comics that help us unpack these myths.

Ultimately, for me, the objective is to figure out how both of these tools – poetry and comics – can be useful in inciting the cognitive shifts necessary to better “see like a pastoralist”.