27 December 2025 - Amber Huff & Linda Pappagallo

Rethinking what we think we know about rangelands and pastoralism

Setting a scene…

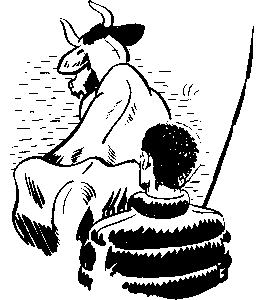

A glowing palette of browns, reds, golds and patchy greens stretches before us as the sun climbs in a cloudless sky. In the distance, a cloud of dust shimmers in the heat haze, churned by hooves as young men guide their hungry animals across the parched, rolling landscape. Low, denuded hillsides seem to bleed from the red scars of erosion gullies. These pastoralists are stoic but stubborn, clinging to an ancient way of life, eking out a meagre living on a tragically degraded terrain. Unrooted, driven by drought, poverty and growing resource scarcity, the search for ‘greener pastures’ is ever more challenging, inviting tension and conflict with farmers, with wildlife, and with state authorities…

The image at the top of this blog post was generated by chatGPT based on the fictional vignette above.

If this scene from anywhere and nowhere feels familiar, it is likely because this vignette draws on a number of narratives, tropes and images that are associated with powerful and enduring myths about pastoralism and rangelands.

Such flawed, incomplete and decontextualised stories, narratives and framings of problems and solutions have profoundly shaped agricultural and development policies, approaches to the management of rangelands – ideas around ‘restoration’, ‘sustainable management’ and ‘development’ – as well as broader societal prejudices against pastoralism and small-scale livestock keepers.

What do we mean by myths?

When we use the term ‘myths’, we are not just referring to things like errors in data, mistakes in reasoning, or even misinformation and false beliefs.

By myths, we mean stories and narratives that are rooted in particular worldviews and that function in society as explanations that shape and justify particular types of social arrangements and courses of action. Stories have the power to shape the data we think is important, inform the frameworks through which we make sense of the world, and the values we prioritise. Myths embody widely held assumptions, received wisdoms and dogmas that carry rhetorical, cultural, scientific and bureaucratic weight.

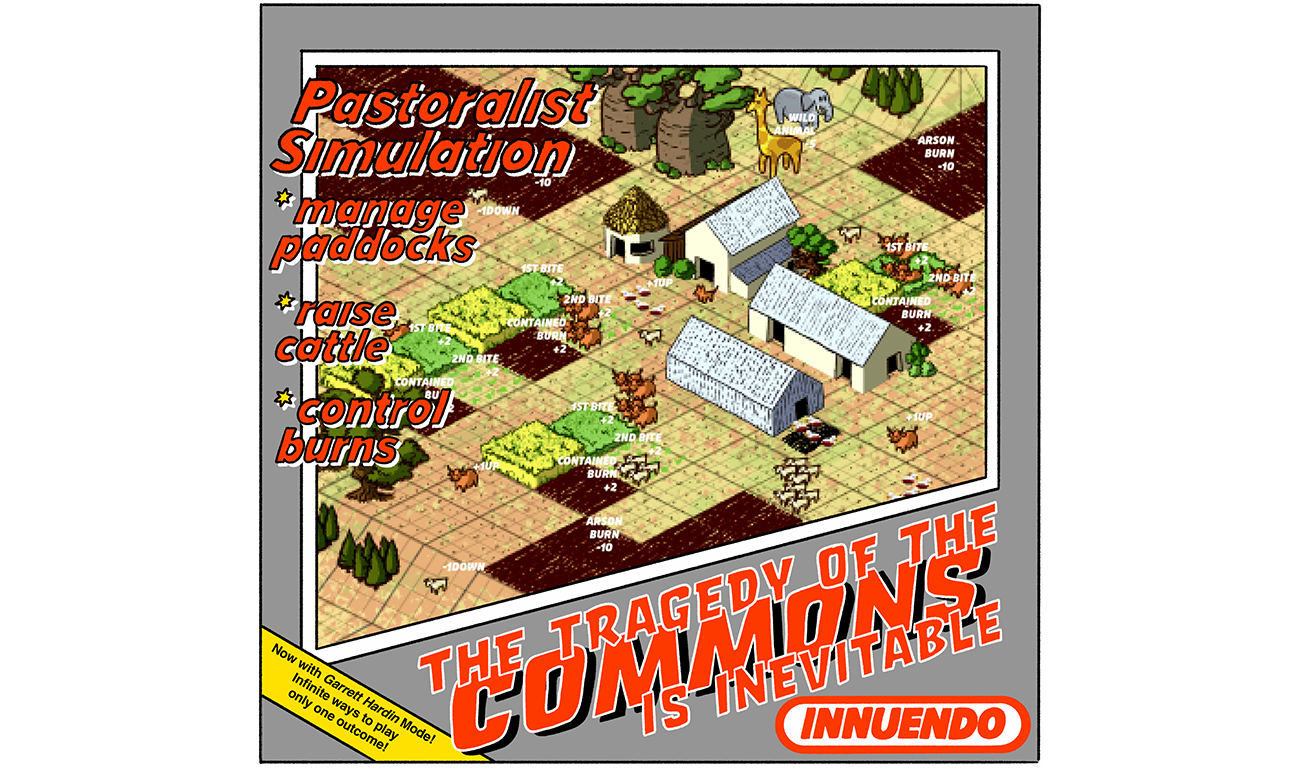

Myths about rangelands include, for example, representations of pastoralism and extensive livestock keeping as an inefficient, environmentally harmful, or outmoded way of life. They reinforce dogmatic beliefs such as the inevitability of the tragedy of the pastoral commons and the association of pastoralist mobility with conflict and insecurity, policy discourses that reify ideas that grassy biomes provide poor habitat for biodiversity or originate from degraded forests or misapply universalised models of environmental change and ecological succession to justify land privatisation, fencing and forced settlement.

Why do myths endure?

Myths are persistent. They gain societal traction and authority as they are repeated and reproduced in public, scientific and policy narratives over time and across sectors. Because of this, myths often go unquestioned despite being overgeneralized, outdated, unjust or just plain wrong. Researchers, journalists, community advocates and others who try to challenge them, even with hard evidence, can run into what seems like a brick wall.

There are many reasons for this. They often originate in a simple story that might seem like common sense. Once a myth takes hold, it can persist due to things like cognitive biases, the common tendency to notice, focus on, and give greater weight to evidence that aligns with what we already believe to be true. Adding to this, myths often contain a ‘grain of truth’, which can add to their persuasiveness. They may resemble phenomena or dynamics observed at some times in some places, but are reproduced in ways that are disconnected from context and often fail to distinguish process, cause and outcome to give the false impression of a general ‘rule’ or ‘pattern’.

Myths become institutionalised, woven into the widely accepted and often inherited logics and values that guide practice and decision-making among members of different knowledge communities. Myths ‘time travel’ and evolve through and within institutional cultures, in governance regimes, research disciplines and educational curricula. They can operate at different scales of decision-making – some are very ‘regional’ or ‘national’ in flavour, while others are more general, with global relevance. They can appear in different forms in different sectors or academic and policy spaces while sharing common underlying motifs.

Myths are often adaptive and can be reproduced in many forms: the framing of a policy brief, a figure in a scientific paper, a photograph caption, a visual metaphor in a documentary, AI-generated overviews from a Google search or results of a Chat GPT query. Myths can be reproduced in ways that are implicit, gesturing toward biases against different ethnic groups, livelihood activities or even regions, or they might be explicit and stated outright. They can be negative and pejorative or romanticising in ways that appear positive. They can appeal to fears – of desertification, drought, poverty, or ‘tragedy of the commons’ scenarios – or to desires for normatively ‘good’ things like food security, sustainable development, and simple, scalable solutions.

What alternatives do we have?

There is a rich legacy of scholarship and activism that have interrogated and challenged dominant myths about rangelands and pastoralism. Scholars of pastoralism, grassland ecologists, social scientists, community advocates, and pastoralists themselves have all contributed rich analyses, vital correctives and strong counter-narratives that subvert myths and reveal the social and ecological complexity, adaptability, governance dynamics and lived knowledge that shape these vital socio-ecological systems.

Their efforts continue to open space for plural perspectives, more grounded and nuanced theoretical understandings and generative cross-disciplinary debates about agrarian change and rangeland dynamics. Cumulatively, this work shows that rangelands and pastoralist systems are extremely variable, landscape dynamics are highly specific to context, and history and politics are always part of the story. Degradation is not inevitable; grasslands are not simply degraded forests; processes of social and ecological change are often non-linear; adaptation and regeneration are integral parts of how these systems function and change.

Such critical work can help us to better understand, for example, why attempts to impose uniform intervention models like fixed grazing management or fire suppression often fail to achieve desired management or restoration outcomes. It is not because so-called ‘local people’ are resistant to change, but because the models themselves are poorly suited to ecological and social realities – existing governance systems, enmeshed social and environmental histories, labour dynamics, situated knowledge, affective relationships and aspirations that influence the myriad micro-choices one makes from day to day, season to season, year to year.

Why we need to rethink what we think we know

Myths are built from constellations of ideas, symbols and stories, but they are not just abstract concepts or flawed theories. They are what social theorists call ‘real abstractions’ – forms of knowledge that arise from objective social structures and very real power relations, that exercise force in the material world, and in turn reinforce these structural relations regardless of an individual’s intention or awareness. Myths don’t just misrepresent facts; they can create and impose truths and ways of seeing and knowing that can reproduce forms of misrecognition and exacerbate power imbalances. Myths leave little room for uncertainty, ambiguity or critical reflection.

In other words, myths have effects that can be difficult to see if you aren’t looking for them, but they are political and have tangible, real-world consequences. Myths warp the lenses through which pastoralism and rangelands are seen, understood, represented and judged by different actors.

This can distort research and funding priorities and create barriers to extending evidence-based and interdisciplinary understandings of complicated social and environmental processes. Distorted understandings can in turn lead to ‘solutions’ that create new problems and risks and reproduce or exacerbate exclusions. Myths shape the parameters of debate and whose claims and knowledge are considered legitimate, who gets to decide what things like governance, sustainability and development should mean in practice, and whose imaginaries of rural futures are considered.

Exploring rangeland myths

The overarching aim of the REPAiR project is to contextualize nature-based intervention in communal rangelands in Southern Africa. But contextualizing restoration initiatives goes beyond specific project settings, intervention landscapes and national policy frameworks. It also requires that we consider how places, people, animals, plants and projects enmesh in broader histories, understandings and knowledge structures.

For these reasons and building on strong complementarities with the 2026 International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists, REPAiR is leading an exciting year-long initiative to explore rangeland myths in global context.

Our aim is not to ‘debunk’ but to disrupt, rethink and galvanize a shift in how we ‘see’ rangelands and pastoralism. Our starting point, building from a rich legacy of scholarship and activism, is to use storytelling and dialogue to create an open and constructively critical space for sharing, learning, reflection and debate, as a generative entry-point for rethinking dominant narratives about rangelands – about livestock, pastoralist livelihoods, agrarian change.

We begin with some key questions.

-

-

- Where do dominant rangeland myths come from and how have they ‘travelled’ and evolved across time and space?

- What forms do these myths take in different places and in different spaces of debate and decision-making?

- Who has benefitted from them, and who has been excluded by them?

- How are they contested, and by whom?

- How are they shaping discourses and approaches to rangeland management and restoration?

- What correctives, context-specific counter-narratives and alternative stories exist, and how should they be amplified?

-

We are excited to invite researchers, artists, writers, practitioners, policy professionals, livestock keepers, managers, herders, traders and anyone with an interest in rangelands, pastoralism and myths about them, to join us.

Further reading

- Research programmes tackling rangeland myths: PASTRES, SPARC and CONDJUST.

- The IIED’s free online course on ‘Pastoralism in Development’.

- ‘When storytelling overcomes the myths of development’ by Philippa Smales, P. (DEVPOLICY Blog, 2018).

- ‘Narratives and policy – What’s the connection?’ by Alex Flynn (Current Conservation, 2009).

- ‘Introduction’ to Political Ecology: Science, Myth and Power, edited by Philip Stott and Sian Sullivan (2000).

- ‘Depicting decline: images and myths in environmental discourse analysis’ by Tor A. Benjaminsen (2021, Landscape Research)

- ‘Myths, challenges and questions on mobile pastoralism in West Asia’ by Taghi Farvar (2003, pages 31-41 in Policy Matters, Issue 12)

Illustration by Tim Zocco, 2025