9 January 2026 - Amber Huff

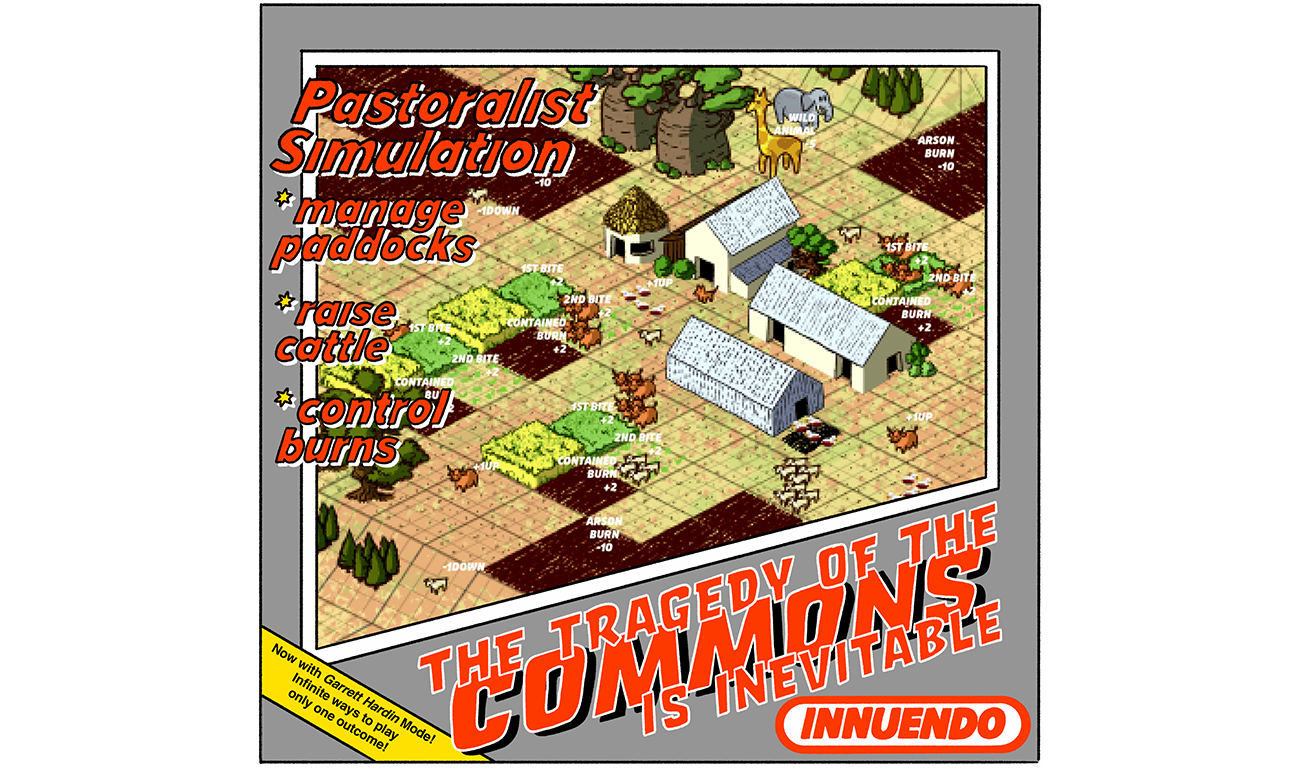

Myth: The tragedy of the commons is inevitable

Exploring the persistence and power of a master myth

‘Picture a pasture open to all…’

These words introduce what is arguably one of the most powerful science fiction stories ever written. It is a parable that takes up just a few inches in an essay titled ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’, published in Science nearly sixty years ago by American ecologist Garrett Hardin.

The essay uses the language of game theory and the metaphor of a local pasture to argue for what Hardin considered a universal truth: that self-interested ‘rational beings’ will inevitably overuse and degrade a resource base because people will always be compelled to consume as much as possible before others can do the same.

As the story goes, everything seems fine while the population of herders is small, but as the population grows and more and more animals are put to pasture, resources grow scarce and the pasture is inevitably destroyed.

In Hardin’s words, ‘freedom in a commons brings ruin to all’, and the only solution is for the state or the market to take charge.

An enduring myth

Most would agree that Hardin’s thesis is flawed, logically inconsistent, and downright dangerous. Its arguments have been discredited by decades of empirical research and an expansive body of literature from the natural and social sciences and humanities challenging its assumptions about human nature, social cooperation, governance, scarcity and sustainability.

Yet paradoxically, the tragedy story continues to circulate and evolve, holding power and authority in institutional knowledge, policy, scholarship and popular culture. It has cultural force and has in many ways taken on a life of its own as an enduring master myth.

As rangeland restoration initiatives proliferate globally and the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists calls attention to the global diversity, importance and governance of the world’s rangelands, we reflect on the myth of the tragedy of the commons as particularly relevant and illustrative of the power and hazards of universalising and reductive stories and the politics they inspire.

A story that tells stories

Much of the cultural force of The Tragedy of the Commons comes from the fact that it’s a story that tells stories. Hardin may have given the ‘tragedy’ its name, but his thesis was built from, re-framed and invoked much older stories and myths that have long shaped how communal lands and people who live in them are ‘seen’, how problems affecting them are perceived, how ‘solutions’ are formulated and whose perspectives, needs and knowledge are privileged.

Legal and philosophical roots

In the early modern period in England, the new ideas about relationships between efficiency, individual property and ‘improvement’ came to dominate agricultural discourse on ‘the commons’. Hobbesian ideas about order and control and Lockean arguments that linked unitary property rights to labour and improvement, gave rise to a widespread view of commons – lands which peasants had long been legally entitled to use and collaboratively manage for grazing, fuel collection and other subsistence needs – as underutilised and ungoverned ‘wastes’.

These stories functioned as economic and moral justification for legal changes to access rights and the violent enclosure of commons in the British Isles, but were also inspired by and in turn provided rhetorical fuel for the expansion of European colonial and imperial projects abroad.

Stories travel

In the context of European colonisation, these stories created a biased filter for how landscapes and society were ‘seen’ by naturalists, social thinkers and administrators. They profoundly influenced colonial agricultural and forestry policies, the evolution of range science and social interventions applied specifically to rangelands and pastoralist peoples around the world.

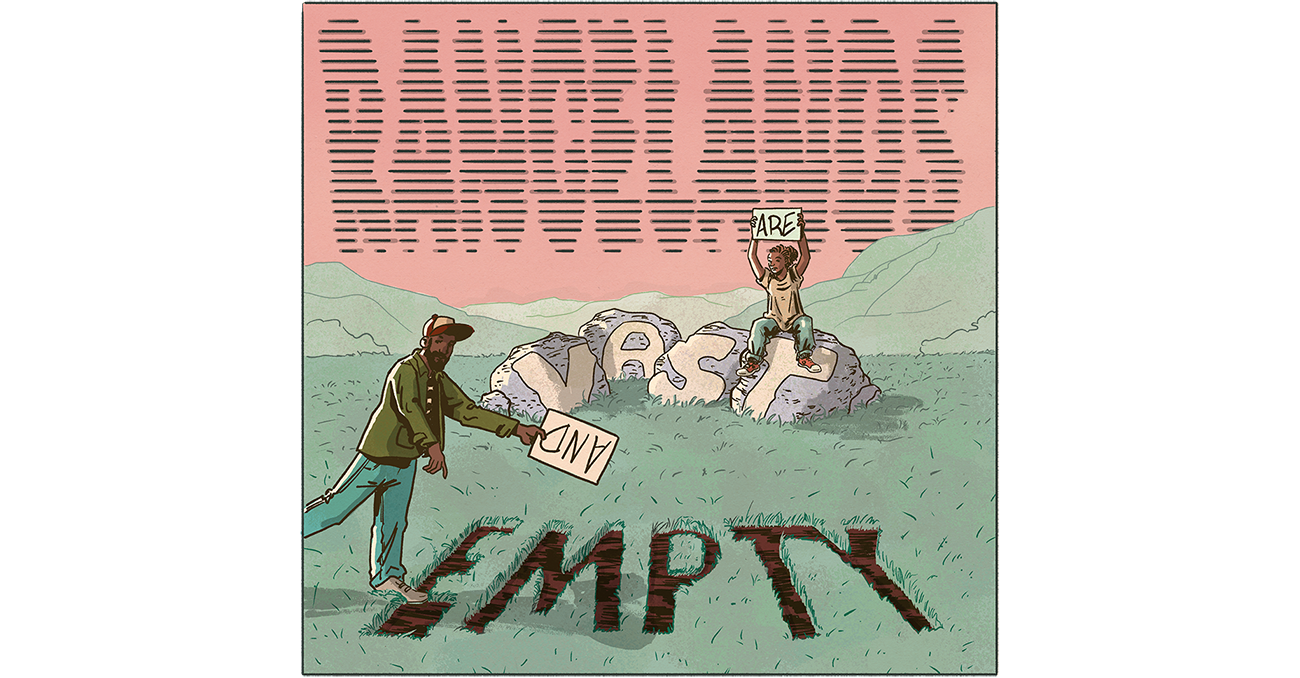

This influence is reflected in exaggerated estimations of anthropogenic deforestation from colonial contexts in India, Southern and Eastern Africa and Asia, and widespread descriptions of grasslands as vast, empty, inefficiently used landscapes damaged by grazing and burning. Systematic misdiagnosis of overgrazing and degradation historically provided a post hoc scientific rationale for decisions shaped principally by political and economic considerations.

Extractive and commercial logics shaped scientific metrics and baselines as well – productivity reckoned as quantified market output rather than less quantifiable or situated values related to things like livelihood security, drought buffering, happiness or social wellbeing. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, generalised formulations of ‘optimal sustainable yield’ within Southern African livestock systems led to widespread prescriptions of privatisation, fenced camps, and controlled livestock numbers favouring private land ownership and commercial production.

Throughout sub-Saharan Africa, existing practices involving mobility, flexible stocking, the use of fire, and shared access were rarely recognised as adaptive strategies in a positive sense. They were instead interpreted as signs of disorder and ‘backwardness’, indicators of problems in need of discipline and rationalisation. Ostensible ‘solutions’ – settlement schemes, biological control, fire suppression, land titling mandates and commercialisation – have had long-term consequences for rangeland ecology and livelihoods, undermining customary knowledge and governance institutions and practices associated with adaptability and resilience, intensifying vulnerabilities and, paradoxically, producing the very forms of damage they claimed to mitigate.

Illustration by Tim Zocco, 2025.

An idea that ‘thinks’ other ideas

The parable of the imaginary pasture stands out in Hardin’s essay, in part because of its relationship to these stories that were already circulating and widely accepted. But Tragedy wasn’t really about the pasture, which only takes up a few inches in the essay — alongside the hazards of free parking meters, loud music, nuclear warfare, human rights conventions and the ‘freedom to breed’. The ‘pasture’ is a metaphor of the planet Earth, and the animals are children. Hardin was attempting a moral intervention in line with what we now recognise as his nativist and white supremacist beliefs and his obsession with the idea that human population growth, particularly in the Global South, would lead to inevitable civilizational collapse.

As a master myth, the ‘tragedy of the commons’ and its pastoral metaphor carry the baggage of these older stories and Hardin’s own biases, yet as a myth it also exceeds them. It is an idea that thinks other ideas, shaping new narratives and political projects while reproducing entrenched structures of power and knowledge. It does this by providing a deceptively simple and ideologically flexible narrative template. Its meaning is not fixed but emerges and evolves through the ways it is interpreted, appropriated and operationalised by different actors and knowledge communities in relation to different phenomena.

This awareness helps explain the synergies the essay helped crystallise when it was published and its afterlife in the ‘enduring crisis moment’ we now find ourselves in.

Tangled tales

Regardless of whether any individual or institution shared or rejected Hardin’s xenophobia and racism, Tragedy’s scientific language and ‘moral’ concerns with population growth, resource scarcity and development geography tapped into a zeitgeist when it was published.

It appealed simultaneously to widespread Cold War fears, the emerging liberal environmentalist movement in the Global North, as well as the concerns of extractive industries and multilateral institutions focused on questions of the so-called ‘limits to (population and economic) growth’ imposed by global carrying capacity and finite natural resources.

The latter two had been strongly influenced by earlier ‘neo-Malthusian’ thinkers who, like Hardin, brought classical Malthusian scarcity economics into biology and ecology through notions of fixed ‘carrying capacity’ at various spatial scales and blended both with implicit and explicit eugenicist and anti-immigrant ideology. This is reflected clearly in Hardin’s solution (coercive control and regulation of human reproduction), his critiques of international aid and human rights conventions, and advocacy for a global ‘lifeboat ethics’.

In parallel, the ‘tragedy of the commons’ was taken up and validated by the neoliberal globalisation movement, justifying transformative policy reforms associated with, among other things, the progressive rollback of state environmental regulations and waves of ‘new enclosures’ involving privatization of land and other natural resources, public goods and services, even knowledge and culture.

Hardin’s pasture metaphor was especially important here. It dovetailed with microeconomic ideas about externalities and market failure and the emerging concept of sustainability that underpinned the development of environmental economics and mainstreaming of market environmentalism.

Fast forward to now.

But haven’t things changed?

Paradigms of development, rangeland ecology and conservation more broadly have undergone massive conceptual, methodological and ethical shifts in recent decades. It is not controversial to say that we know Hardin was wrong. That fencing and enclosure are violent. That socio-ecological dynamics and governance arrangements are diverse, variable, often messy, always changing and always enmeshed in local and broader histories and political economies. That ‘sustainability’ is contested and contingent. We valorise situated knowledge and just outcomes.

Yet the ideas that privatisation of resources and marketisation of nature will incentivise environmental stewardship, address externalities and thereby ‘green’ economic growth have come to dominate responses to all manner of challenges at multiple policy levels – from poverty to pollution, biodiversity loss, desertification and global climate change. And inherited imaginaries continue to shape and constrain the lenses through which rangeland landscapes are seen and represented as overstocked, inefficiently used, poorly governed and already degraded, echoing earlier politics of enclosure, simplification and control.

These ideas can come together ‘where the rubber hits the road’ as trends in rangeland restoration, conservation, economic development, climate finance and rangeland carbon markets are applied in real world spaces. Assumptions about rural life, markets, drivers of environmental change or that external expertise and intervention are required can prime us to ‘see’ an unfolding tragedy.

Ethical practice matters immensely, but systemic factors can be difficult to navigate and can create risks – of extending and reproducing political, economic and knowledge hierarchies that privilege external investment and expertise, commodified forms value in nature, and superficial approaches to participation. These can weaken and marginalise, rather than strengthen, adaptive and relational forms of stewardship.

Beyond the grand narratives

We might not believe in the tragedy of the commons, but it still believes in us. Moving beyond it is not simply a matter of correcting flawed theory, offering yet more evidence, or proposing alternatives that fit comfortably within its logical architecture. Rather, it lies in learning to see universalising myths for what they are, in unsettling and refusing the stories behind the stories, and in breaking the threads that bind their continuities.

Storytelling, situated and relational approaches, and perspectives on commoning offer more open frameworks for this sort of recognition and creative disruption, inviting us to question myths, see through plural lenses, to amplify plural knowledges and experiences, and see an expanded range of possibilities. The work of re-seeing is essential to galvanising a real shift, opening up more plural, situated, generative and relational ways of understanding lived and often messy realities of governance, ecology, and care.

Want to discuss the ‘tragedy of the commons’? Join our first ‘rangeland myths‘ online conversation of 2026, focused on the myth of the ‘tragedy of the commons’ on Thursday, 22 January from 11:00 am – 12:30 pm GMT with speaker Frank Matose and co-chairs Amber Huff and Farai Mtero.

We warmly invite anyone with an interest in rangelands, pastoralism and myths about them, to join, share your stories and rethink how we ‘see’ rangelands and pastoralism. Register to join using the Eventbrite link below!

Further reading

- ‘Debunking the tragedy of the commons’, by Fabien Locher (CNRS news, 2018)

- ‘Introduction: new enclosures’, by Ashley Dawson (New Formations, 2010)

- ‘Map, territory, story’, a comic by Tim Zocco & Amber Huff for Future Natures (2023).

- ‘Why can’t we get past the “tragedy of the commons”?’ & ‘It’s not always a collective action problem’ by Lance Robinson, Deliberative Landscapes Wanderer (2020).

- ‘High Modernism made our world: on James Scott and technology’ by Henry Farrell (Programmable Mutter, 2024)

- ‘Finding a way: Will Peoples’ Responses to the Emergencies of the Coming Decades be Warm? Or Cold?’, by Nora Bateson & Mamphela Ramphele (first published in Medium, reposted by Club of Rome, 2020)

- ‘Peter Linebaugh on what the history of commoning reveals,’ by David Bollier (Frontiers of Commoning, 2021)

Read more

The REPAiR Project blog brings diverse views from our project team and collaborators into conversation around key themes and ideas.